| Cellular and Molecular Medicine Research, ISSN 2817-6359 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cell Mol Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://cmmr.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 3, Number 2, December 2025, pages 25-34

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: An Expanded Meta-Analysis of Metabolic Outcomes

Independent Researcher, Port St. Lucie, FL 34952, USA

Manuscript submitted October 20, 2025, accepted December 15, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in People With HIV

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/cmmr114

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: As a consequence of modern antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens, people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are disproportionately affected by weight gain and associated cardiometabolic comorbidities. Although glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have emerged as efficacious weight loss modalities among the general population, little is known regarding the safety and efficacy among people with HIV undergoing treatment with ART.

Methods: This study extended previous meta-analytic work evaluating the metabolic efficacy of GLP-1 RAs in people with treated HIV, due to a paucity of included studies under the initial protocol. A total of 10 studies, including both clinical trials and retrospective observational data, were analyzed to assess changes in weight, body mass index (BMI), and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Meta-analyses were performed using random-effects models with robust analyses for heterogeneity and bias, as well as moderator analyses.

Results: GLP-1 RA use was associated with a statistically significant reduction in weight (dunbiased = -0.687, 95% confidence interval (CI): -0.908 to -0.467; P < 0.001), BMI (dunbiased = -0.693, 95% CI: -1.008 to -0.378; P < 0.001), and HbA1c (dunbiased = -0.539, 95% CI: -0.727 to -0.352; P < 0.001). Significant heterogeneity was observed across all outcomes, though publication bias was not consistently supported. Moderator analyses revealed greater weight and BMI reductions in clinical trials and in studies with a lower proportion of participants with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Dulaglutide use was associated with blunted effects across weight and BMI outcomes compared to semaglutide and liraglutide. Notably, semaglutide use did not yield significantly greater metabolic improvements relative to other GLP-1 RAs. Correlational analyses supported the role of T2D status and dulaglutide use in moderating treatment response. These findings align with existing data in the general population, where non-diabetic individuals and certain GLP-1 RAs (e.g., semaglutide) typically show greater efficacy.

Conclusions: Given the emerging concern around ART-induced weight gain and associated cardiometabolic risk, GLP-1 RAs may offer a promising therapeutic strategy in this high-risk population. Further research is needed to evaluate long-term safety, optimal agent selection, and patient-level predictors of treatment response.

Keywords: GLP-1 agonists; HIV; Weight loss; Antiretroviral therapy; INSTI; Semaglutide

| Introduction | ▴Top |

In the modern era of antiretroviral therapy (ART), people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have continued to experience a relative increase in life expectancy, now comparable to that of the general population [1]. As a result, cardiometabolic comorbidities have emerged as leading contributors to long-term morbidity and mortality in this population [2-5]. Certain ART regimens, particularly those including integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), and select protease inhibitors, have been independently associated with weight gain compared to other ART regimens and age-related weight gain among the general population [6-9]. Consequently, people with treated HIV may also be disproportionately affected by increases in insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [2-5]. Given that HIV infection has been independently associated (i.e., with or without ART) with increased risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities, these iatrogenic effects have sparked increased attention toward risk-mitigating strategies that can be safely co-administered in the context of ART [10, 11].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have demonstrated significant efficacy in improving glycemic control and inducing weight loss in the general population [12, 13]; resultantly, these drugs have been increasingly used in recent years to treat obesity and T2D [14, 15]. However, the safety and effectiveness of GLP-1 RAs have not been sufficiently evaluated in people with HIV. Several factors, such as altered hepatic metabolism, ART-induced enzymatic changes, and immune activation, could plausibly influence GLP-1 RA pharmacodynamics in this population despite differences in metabolic clearance (e.g., CYP450-mediated oxidation vs. enzymatic degradation and renal excretion) [16, 17]. Moreover, regulatory data on the concomitant use of ART and GLP-1 RAs are limited, and formal clinical guidelines for GLP-1 RA use in people with HIV have not yet been established.

A prior systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the limited but emerging body of literature on GLP-1 RAs in this population, analyzing metabolic outcomes (i.e., weight, body mass index (BMI), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)) across five studies [18]. That review noted modest to strong effects for weight loss and glycemic improvement but was ultimately constrained by a small number of applicable studies and considerable methodological heterogeneity. Additionally, the first review suggested a non-significant effect of INSTI use on GLP-RA efficacy, and that semaglutide elicited superior metabolic outcomes versus other GLP-1 RAs (i.e., dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, tirzepatide). However, it was postulated that the study heterogeneity may have confounded these outcomes. To further contextualize and extend these findings, this follow-up analysis incorporates five additional sources, including three peer-reviewed observational studies and two conference abstracts with preliminary study data, identified through structured and extensive searches on Google Scholar, Google, and through analysis of pre-existing literature reviews. Though not identified via formal Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology as used in the initial study, these additional sources add clinical relevance and breadth to an otherwise sparse evidence base, which is particularly important given the vast increase in GLP-1 RA use since obtaining US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to treat overweight and obese individuals without T2D [15].

The primary aim of this extended analysis was to characterize and validate the effects of GLP-1 RAs on metabolic outcomes in people with treated HIV, including weight, BMI, and HbA1c, across a broader range of real-world and experimental settings. This analysis does not repeat the full systematic review process but instead builds upon previously established methods to further delineate the therapeutic potential and limitations of GLP-1 RAs in the context of HIV-related care. Because two included sources were conference abstracts, their preliminary nature introduces inherent limitations related to data completeness and peer-review status. However, their inclusion offers clinically relevant insight into a rapidly evolving therapeutic area with limited data.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and objectives

This study extends a previously published systematic review and meta-analysis, which synthesized human clinical data on GLP-1 RA use in people with HIV [18] across five studies [19-23]. The current analysis incorporates five additional studies, each identified after the original review period, selected to provide further insight into the metabolic efficacy of GLP-1 RAs in this population [24-28]. The primary outcomes evaluated were changes in weight, BMI, and HbA1c. The primary objective was to describe and quantify the overall metabolic effects of GLP-1 RAs in people with HIV across a larger sample of studies and individuals. The secondary objective was to further scrutinize covariates identified in the initial analysis that may influence the use of GLP-1 RAs in this population, such as baseline BMI, INSTI use, and GLP-1 RA variance.

Search strategy and study inclusion

The original systematic search was conducted using PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov through January 2025, following PRISMA 2020 guidelines, as described in the initial study [18]. In the current study, additional sources were identified via pre-existing literature reviews, as well as extensive manual searches of Google Scholar (for publications) and Google (for publications or conference abstracts) using combinations of the terms: “GLP-1 agonist,” “HIV,” “antiretroviral therapy,” “semaglutide,” “liraglutide,” “dulaglutide,” “tirzepatide,” and “tirzepatide.” Inclusion criteria were: 1) original clinical data on humans with HIV receiving GLP-1 RAs; 2) reported outcomes related to weight, BMI, or HbA1c; 3) no confounding from additional antihyperglycemics in aggregate analyses; and 4) available data could be restructured uniformly into mean and standard deviation. Five additional studies (three peer-reviewed, two conference abstracts) were included, and one additional study (conference abstract) was excluded from this analysis due to a lack of comparable data (i.e., only contrast-level data instead of absolute changes) [29]. The five additional studies were not included in the original analysis due to either the date of publication, exclusion based on pre-specified criteria at that time (e.g., peer-reviewed research), or because they were unavailable on the PubMed database used for the initial study.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data from the five additional studies were extracted manually. All data were collected and organized using Microsoft Excel. Collected data were reorganized into mean and standard deviation to align outcomes with those included in the original meta-analysis. Where appropriate, weighted averages were calculated and stratified by drug class or study type. All data analysis was conducted using Jamovi (V 2.6.26.0), an open-access analysis platform built upon R programming. The esci module was used to establish the effect size for each study and outcome, and to conduct the initial moderator analyses. The MAJOR module was used for meta-analysis of primary outcomes and moderators using established effect sizes, including the creation of forest plots.

After organizing the three primary outcomes (weight change, BMI, HbA1c) into mean and standard deviation, all values were initially analyzed and reformatted into a bias-adjusted effect size (Cohen’s d (dunbiased), or Hedge’s g) using a random-effects model to account for study heterogeneity. These effect sizes then underwent meta-analysis to evaluate the cumulative effect, alongside further evaluation of heterogeneity and study bias. Heterogeneity significance was established based on composite scores via Tau, Tau2, I2, H2, R2, and Q values. Study bias was evaluated using Fail-Safe N, Kendall’s Tau, and Egger’s tests. For moderator analyses, variables were stratified based on median values and/or subjective thresholds based on industry standards (e.g., considering a BMI of 30 for obesity) or practicality (e.g., for INSTI use; semaglutide use in pooled studies) and the availability of data from the included studies. For example, INSTI use was stratified using over or under 50% (the majority of participants) in the moderator analysis for weight change; however, this analysis was not possible for BMI or HbA1c due to a limited sample and therefore, was adjusted to the median value of 82.4%. A similar approach was used when analyzing baseline BMI as a moderator. Moderator meta-analysis was subsequently conducted to visualize the influence of six moderators. Lastly, regression analysis was conducted to identify any notable correlations between descriptive variables and the three primary study outcomes.

Ethical considerations

This study serves as an extension of previously approved secondary research and does not involve the collection or use of any new or identifiable data. All data were extracted from publicly available, peer-reviewed sources. The study remains consistent with the original Institutional Review Board-exempt protocol approved by the Keiser University Institutional Review Board in the initial study.

| Results | ▴Top |

In total, 10 studies underwent meta-analysis. Of the three primary outcomes, only weight change (kg) could be evaluated using all 10 studies. BMI was evaluated across seven studies, and HbA1c in nine. These studies collectively included 889 people with HIV, both with and without T2D. Studies exhibited considerable variance across baseline population characteristics (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies |

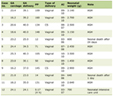

Overall, GLP-1 RA use demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in weight (kgs) across all studies (dunbiased -0.687; 95% confidence interval (CI): -0.908 to -0.467; P < 0.001). Of note, composite study heterogeneity was statistically significant (P < 0.001) for this parameter; no statistically significant publication bias was reported. Notably, all 10 studies demonstrated a negative effect (reduction in weight), with only one study [19] exhibiting a positive variance (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Forest plot: weight change (kg). The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for weight change (kg) associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence intervals. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; RE: random effects. |

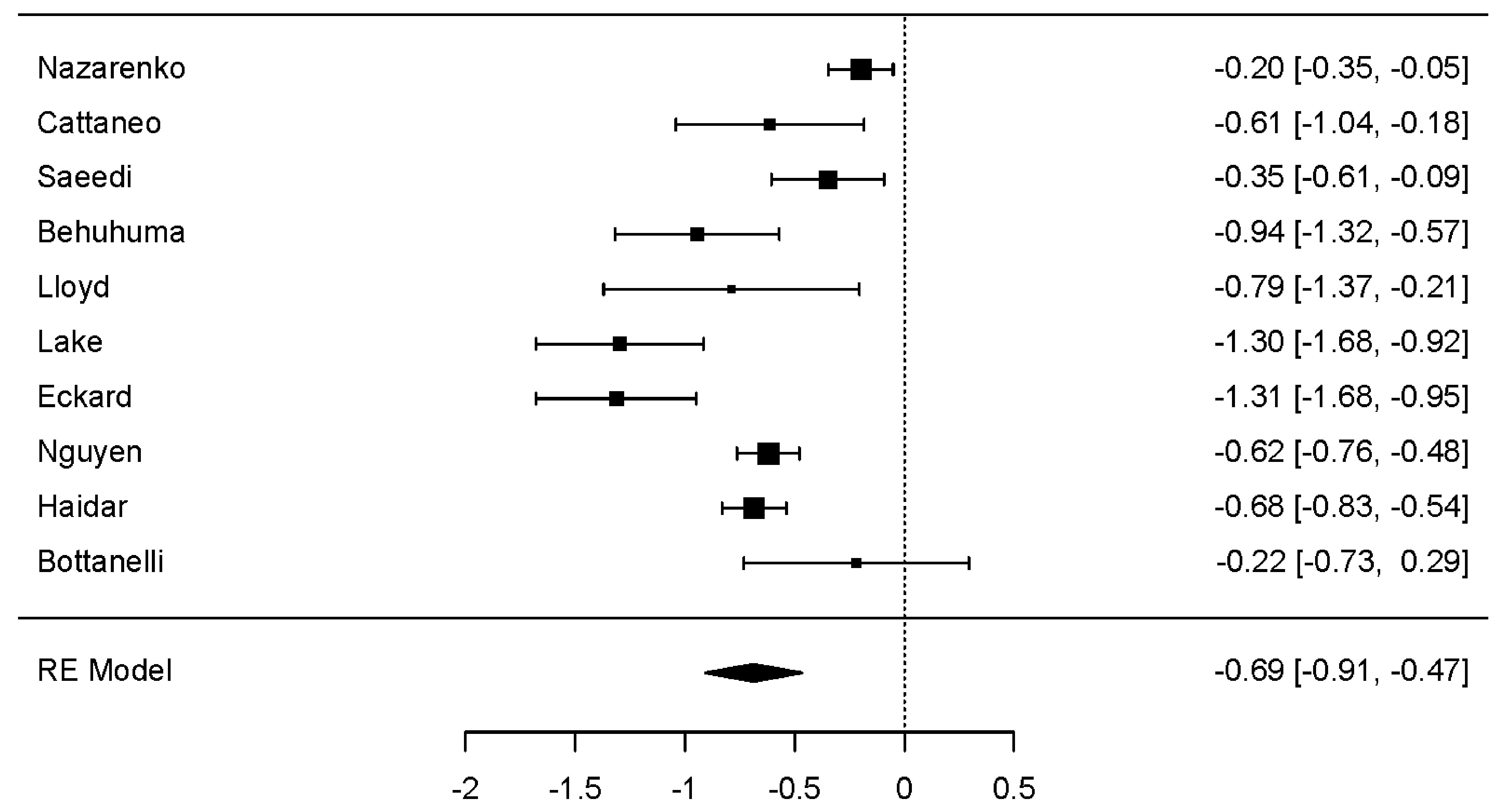

Across seven studies, a statistically significant reduction in BMI was observed (dunbiased -0.693; 95% CI: -1.008 to -0.378; P < 0.001). As with weight change, significant heterogeneity was demonstrated (P < 0.001), but with no statistically significant evidence of publication bias. All seven studies exhibited a negative overall effect (reduction in BMI), with two studies recording positive variance (Fig. 2) [19, 24].

Click for large image | Figure 2. Forest plot: BMI change. The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for BMI change associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence intervals. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; BMI: body mass index; RE: random effects. |

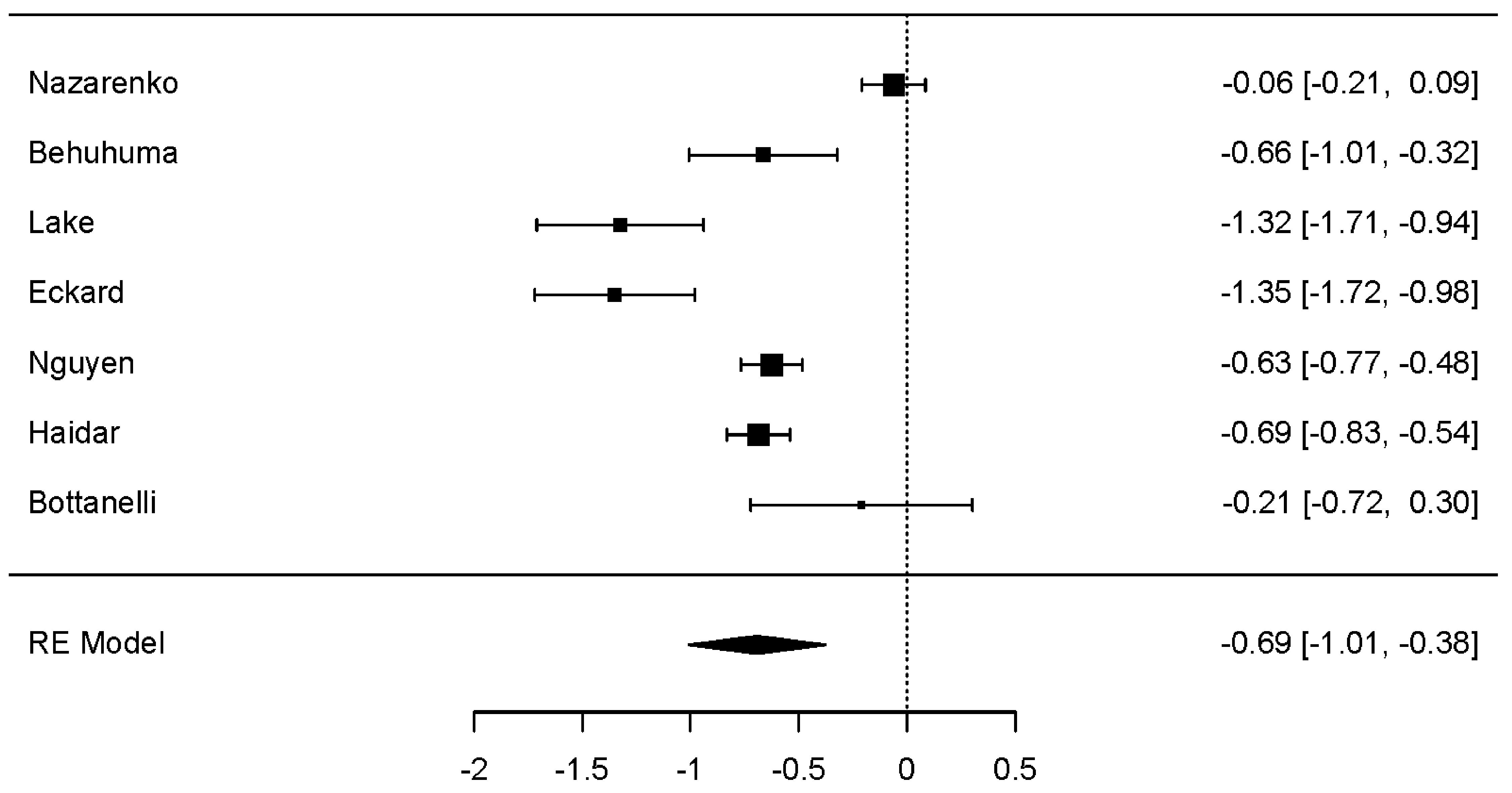

Change in HbA1c was evaluated to assess the metabolic efficacy of GLP-1 RAs with or without weight loss. Across nine studies, a statistically significant negative effect on HbA1c was observed (Fig. 3) (dunbiased -0.539; 95% CI: -0.727 to -0.352; P < 0.001). Like both weight-related outcomes, HbA1c was associated with statistically significant heterogeneity (P < 0.001). Egger’s test suggested potential publication bias (P < 0.05); however, neither the Fail-Safe N nor Kendall’s Tau tests supported this result.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Forest plot: HbA1c change. The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for HbA1c change associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence intervals. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; GLP-1 RAs: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; RE: random effects. |

Secondary analyses

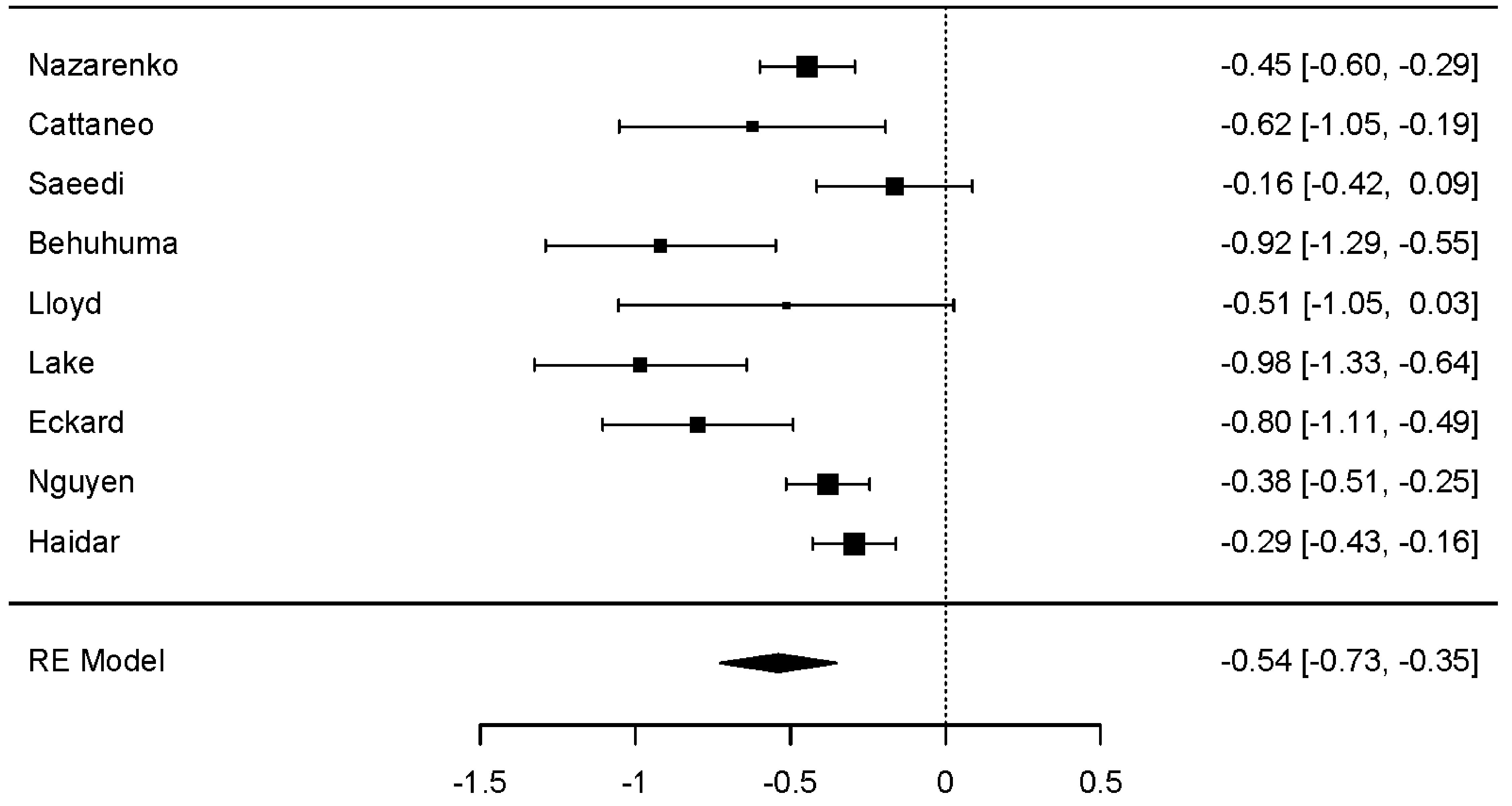

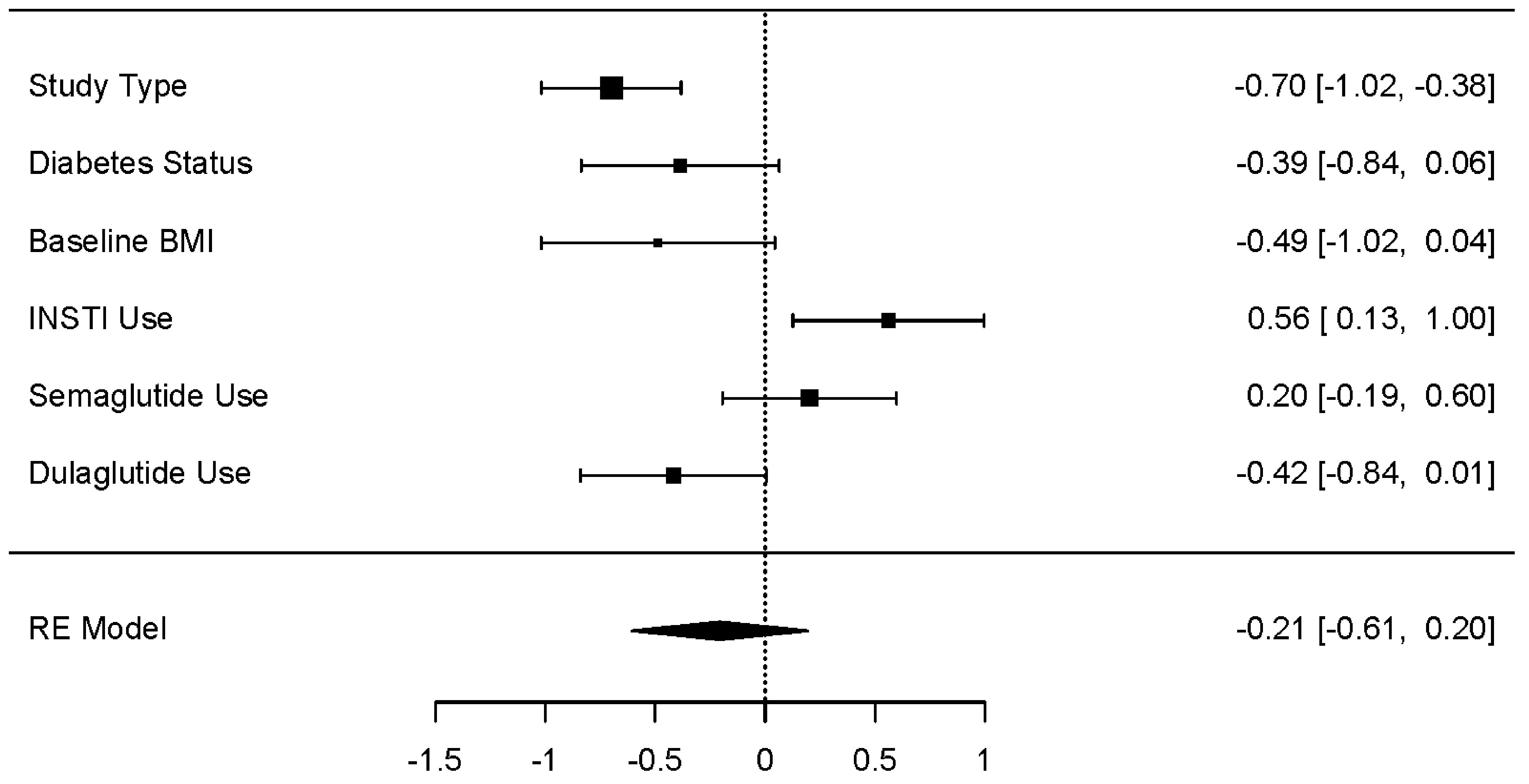

Moderator analysis was conducted independently across all three main metabolic outcomes; covariates included study type (i.e., clinical trial versus observational), baseline BMI, T2D status, INSTI use, and semaglutide use. For weight change (kg), a statistically significant effect was observed for study type (P < 0.001) and INSTI use (P < 0.05), with greater weight loss observed in clinical trials, and in studies in which more than 50% of the participants used an INSTI-based ART regimen. A trend towards greater weight loss was observed in studies with fewer diabetics (P = 0.093), with BMI greater than 31 (P = 0.073), and those who did not use the GLP-1 RA dulaglutide (P = 0.054). Semaglutide use was not associated with a significant effect on weight (kg) (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Moderator effect sizes for weight (kg). The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for moderators of weight change (kg) associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence intervals. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitor; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; RE: random effects. |

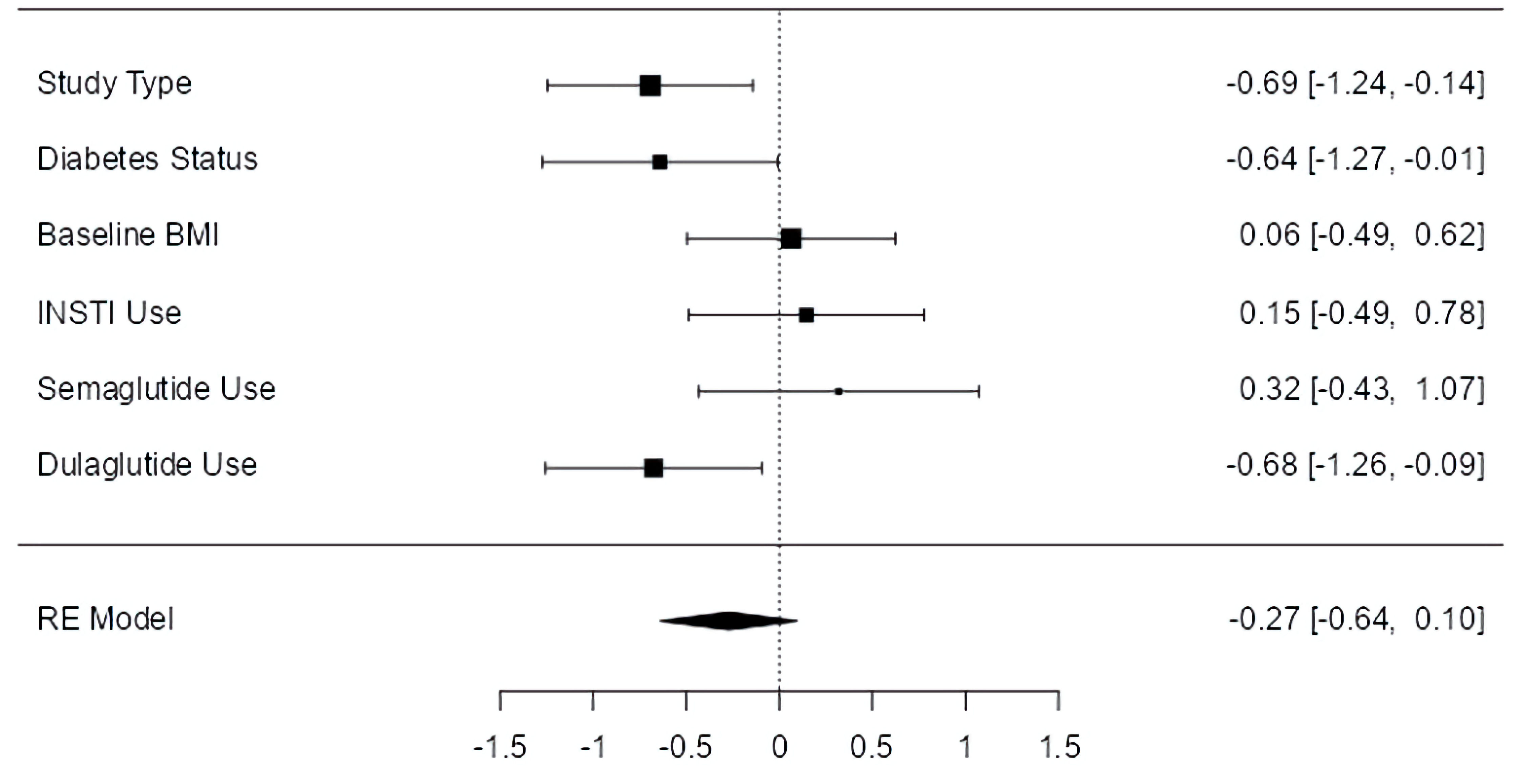

For BMI, a significant effect was observed for study type (P < 0.05) and T2D status (P < 0.05), with greater weight loss associated with clinical trials and studies involving fewer individuals with T2D. Moreover, dulaglutide demonstrated a significant effect on BMI (P < 0.05), favoring alternative GLP-1 RAs (Fig. 5). Neither baseline BMI, INSTI use, nor semaglutide was associated with a significant effect on BMI; however, due to the absence of three studies, the baseline BMI and INSTI use thresholds were higher (median values) than those used for weight change, with BMI of 34.2 kg/m2 and INSTI use of 82.4%, respectively.

Click for large image | Figure 5. Moderator effect sizes for BMI. The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for moderators of BMI change associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence intervals. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; RE: random effects. |

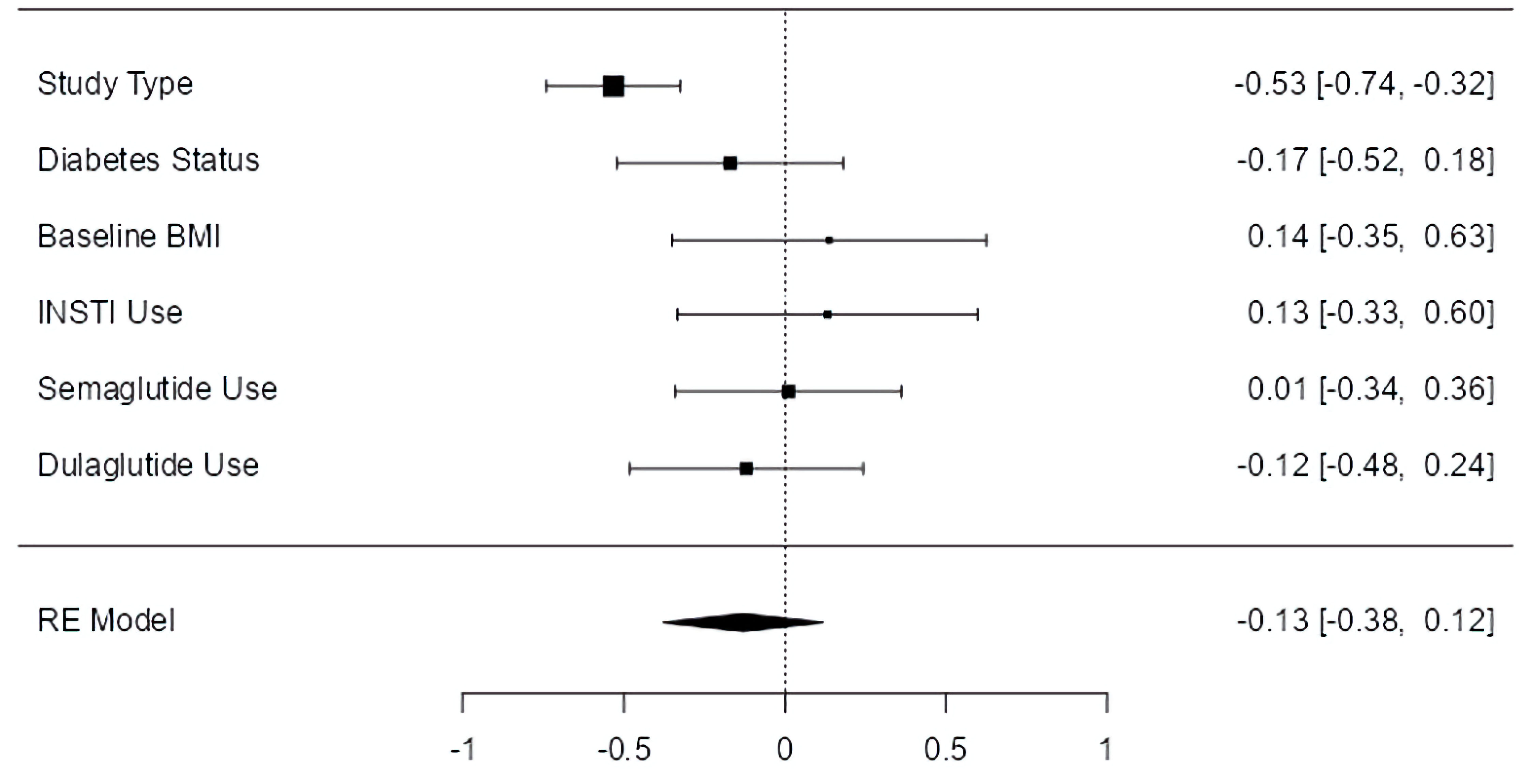

Only study type was associated with a significant effect on HbA1c (P < 0.001), which continued to favor clinical trials over observational studies. Semaglutide use, dulaglutide use, T2D status, baseline BMI, and INSTI use had no notable effect on HbA1c (Fig. 6).

Click for large image | Figure 6. Moderator effect sizes for HbA1c. The forest plot illustrates the random-effects meta-analysis model for moderators of HbA1c change associated with GLP-1 RAs among people with HIV. Values are presented as effect sizes (dunbiased) and 95% confidence interval. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitor; BMI: body mass index; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; RE: random effects. |

Correlations

To further review relationships between the primary metabolic outcomes and covariates, correlations were analyzed between each primary outcome and study duration, percent of participants with T2D, baseline BMI, percent male participants, percent female participants, mean age, percent of participants using an INSTI, percent of participants using semaglutide, percent of participants using dulaglutide, and percent of participants using liraglutide. For weight gain, a significant positive correlation was observed with the percentage of participants with T2D (r = 0.752; P < 0.05) and the percentage of participants using dulaglutide (r = 0.643; P < 0.05). Similar correlations were established between BMI and T2D (r = 0.824; P < 0.05) and the percentage of participants using dulaglutide (r = 0.818; P < 0.05). For HbA1c, a significant positive correlation was only observed with percent of male participants (r = 0.677; P < 0.05).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This updated meta-analysis provides the most current synthesis of GLP-1 RA efficacy among people with HIV, specifically aiming to validate pre-established effects on weight change, BMI, and HbA1c. With the inclusion of five additional studies beyond those assessed in the original systematic review and meta-analysis, this update offers invaluable context into the use of GLP-1 RAs in a population increasingly affected by obesity and related cardiometabolic comorbidities.

Consistent with prior findings, GLP-1 RA use was associated with statistically significant reductions in weight, BMI, and HbA1c. Notably, all 10 studies demonstrated a reduction in body weight, with effect sizes falling within a moderate-to-large range, reinforcing the reliability and reproducibility of this outcome despite differences in study design and population characteristics. This effect remained significant despite notable heterogeneity across the studies included and their associated outcomes. The magnitude and directional effect of GLP-1 RAs on BMI mirrored that of weight loss, further supporting the efficacy of these agents. Moreover, the observed reduction in HbA1c across nine studies further supports the dual metabolic benefit of GLP-1 RAs in this population, including in studies that enrolled participants without T2D. The substantial heterogeneity recorded across outcomes likely reflects differences in study design (e.g., study type, sample size, follow-up duration), demographic characteristics (e.g., baseline BMI, gender, T2D prevalence), and pharmaceutical variations, as well as unmeasured confounding inherent to aggregated data. Because these factors cannot be modeled simultaneously without individual-level data, the random-effects approach was used to more appropriately account for this between-study variability. Although substantial heterogeneity was observed, the consistently negative direction and moderate-to-large magnitude of effect sizes across nearly all studies support the robustness of the observed metabolic benefits.

Moderator analyses identified notable trends based on study type, T2D status, INSTI use, and dulaglutide use. Across all three primary endpoints, clinical trials demonstrated significantly greater effects than retrospective studies, suggesting that study design may meaningfully influence perceived efficacy. The current study added a third clinical trial, albeit with preliminary data, which reinforced trends observed in the initial analysis despite a modest study duration (12 weeks) [27]. The improved efficacy in clinical trials may be due to selection criteria, adherence monitoring, or data completeness; however, these results also raise questions about the translational gap between clinical trial efficacy and real-world effectiveness in people with HIV.

Another key finding was the association between T2D status and attenuated weight and BMI reductions. Studies with a higher proportion of participants with T2D trended toward smaller treatment effects, a finding also supported by correlation analyses. The blunted efficacy of GLP-1 RAs toward weight loss among diabetics is consistent with data observed among people without HIV [12, 30]. Thus, GLP-1 RAs may have particular value in non-diabetic people with HIV, who may continue to be otherwise underserved by pharmacologic weight management strategies, based on reported trends of GLP-1 RA use among diabetics with HIV [31].

Interestingly, INSTI use appeared to moderate greater reductions in weight, contrasting the original analysis, which demonstrated no significant difference in weight loss between INSTI-based regimens and non-INSTI-based regimens. Although data are limited to suggest a definitive effect between INSTI use and weight loss, this finding suggests that GLP-1 RAs could be a foundational intervention to counteract the known associations between INSTIs and weight gain, particularly in real-world settings. However, because this moderation effect was established based on study-level rather than patient-level data, it should not be interpreted as a causal or regimen-specific interaction; instead, it may reflect differences in underlying cohort characteristics that cannot be accounted for without individual-level adjustment. Additional studies are needed to confirm the moderating effect of INSTI-based ART regimens on GLP-1 RA efficacy, particularly considering the widespread use of INSTIs in first-line HIV therapy [32]. Importantly, future studies should more thoroughly stratify the specific INSTI used, given demonstrated differences in weight gain after ART initiation between modern INSTIs such as dolutegravir (DTG) and raltegravir [7, 33].

Dulaglutide use was also associated with weaker effects on both weight and BMI when compared to other GLP-1 RAs, a pattern that emerged in both moderator and correlation analyses. These data may support the evolving preference for longer acting and more potent agents (e.g., semaglutide) in managing body weight and glycemic efficiency. This relationship was not directly observed in the initial meta-analysis but supports data among the general population demonstrating improved metabolic outcomes with semaglutide or other GLP-1 RAs compared to dulaglutide [34, 35]. However, it should be noted that the use of semaglutide did not independently moderate outcomes in this analysis. Yet, semaglutide’s once-weekly dosing structure also offers a practical advantage over daily dulaglutide or liraglutide for people with HIV, who often face a daily pill burden. Notably, tirzepatide remains understudied in people with HIV, but limited data have demonstrated noninferior outcomes to semaglutide among this population [23].

Finally, the correlation between HbA1c reduction and percentage of male participants (r = 0.677) warrants further investigation. Whether this reflects biological sex differences in drug metabolism, ART interaction, or unmeasured behavioral factors (e.g., medication adherence, diet, activity level) is currently unclear.

The available studies primarily reflect cohorts from high-income settings and include a higher proportion of older and male participants, and those on INSTI-based regimens, which may limit generalizability to younger individuals, women, or people with HIV in low- and middle-income countries, where metabolic risk profiles and ART patterns may differ. Yet, the totality of these findings is especially relevant given ongoing concerns regarding weight gain in people with HIV. Weight increases of clinical significance have been observed for up to 2 years following initiation of certain antiretroviral drugs, most notably with bictegravir, DTG, and TAF [6, 7, 8, 9, 33]. While these drugs are now among the most widely prescribed, the long-term metabolic implications of sustained or cumulative ART-related weight gain are unknown with these agents, largely due to more recent (as recent as 2018) FDA approvals [36]. It is plausible, however, that excess weight contributes to a compounded risk of cardiometabolic comorbidities, including T2D and ASCVD, among people with HIV over time, given known associations between ART and increased risk of such morbidities.

Although lifestyle modification (e.g., physical activity, dietary intervention) should remain the first-line recommendation, existing data suggest that many people with HIV do not initiate or sustain meaningful behavioral changes to successfully manage body weight despite a majority (96%) acknowledging the health benefits [37]. In this context, GLP-1 RAs may serve as an effective short- or intermediate-term intervention to counteract ART-associated weight gain. Several studies in this analysis reported weight loss exceeding 5 kg in 1 year or less; weight loss of this magnitude may offer a clinically meaningful reduction that could be especially valuable when implemented early in the trajectory of weight gain. Moreover, emerging evidence also suggests a potential mortality benefit associated with GLP-1 RA use among certain high-risk subgroups of people with HIV, potentially reflecting improvements in cardiometabolic profiles; however, these findings require confirmation in prospective studies and in analyses stratified by cardiovascular risk factors [38].

Unlike ART, weight loss pharmacotherapy with GLP-1 RAs does not require lifelong use; short courses may be sufficient to achieve or maintain weight loss targets in clinically appropriate patients. Given the escalating use of GLP-1 RAs in the general population and the mounting metabolic challenges faced by individuals with HIV, further research is needed to identify optimal patient selection criteria, treatment durations, and long-term outcomes in this unique context. Moreover, further reporting on adverse effects is necessary to better understand the likelihood and severity of effects for people with HIV. Although data remain vastly limited, some immunologic and hepatic alterations have been reported in this population [18].

Conclusions

This is the largest meta-analytic assessment to date of GLP-1 RA effects on weight, BMI, and HbA1c in people with HIV, integrating both peer-reviewed and emerging clinical data. The findings reinforce consistent metabolic benefit across metabolic outcomes observed in the initial meta-analysis. Although overall metabolic benefit was observed, the findings support superior outcomes in clinical trial settings, among non-diabetics, and with alternatives to dulaglutide (e.g., semaglutide, liraglutide). Importantly, this study reinforced favorable metabolic outcomes with GLP-1 RA regardless of ART class used, with some evidence suggesting improved weight loss outcomes in the context of INSTIs. These insights may help clarify when and for whom GLP-1 RAs may offer the greatest metabolic advantage in the context of HIV, particularly considering growing concerns about ART-associated weight gain.

As people with HIV live longer, the need for therapies that mitigate secondary cardiometabolic risk without imposing long-term medication burden or cost barriers has become increasingly important. GLP-1 RAs, especially once-weekly formulations like semaglutide, offer a time-efficient and potentially high-impact option to counteract ART-associated weight gain, which is increasingly recognized as a chronic consequence of ART. Although long-term safety data remain limited for GLP-1 RAs in this population, short-to-intermediate term interventions may be sufficient to attenuate the compounding risks of obesity, T2D, and ASCVD in this population. Moreover, the existing data suggest relative safety for up to 25 months of GLP-1 RA use. As data on newer GLP-1 RA agents (e.g., tirzepatide) become more available, additional research should evaluate their comparative effectiveness and factors affecting real-world implementation, including cost, access, practical limitations, and regulatory considerations, specifically in the context of HIV care.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This study was conducted without any financial support.

Conflict of Interest

The author of this study, Thomas Barnett, DHSc, is an independent researcher and has no conflict of interest associated with this publication.

Informed Consent

Given the use of secondary data, informed consent did not apply to the current study.

Author Contributions

Thomas Barnett, DHSc, was the sole author for the current study, including all writing and data analysis.

Data Availability

The data used in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ART: antiretroviral therapy; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI: body mass index; DTG: dolutegravir; FDA: US Food and Drug Administration; GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitor; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; T2D: type 2 diabetes; TAF: tenofovir alafenamide

| References | ▴Top |

- Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Alexeeff SE, Anderson AN, Hechter RC, Hu H, Lam JO, et al. Comparison of overall and comorbidity-free life expectancy between insured adults with and without HIV infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207954.

doi pubmed - Bares SH, Wu X, Tassiopoulos K, Lake JE, Koletar SL, Kalayjian R, Erlandson KM. Weight gain after antiretroviral therapy initiation and subsequent risk of metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78(2):395-401.

doi pubmed - Rebeiro PF, Jenkins CA, Bian A, Lake JE, Bourgi K, Moore RD, Horberg MA, et al. Risk of incident diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and their relationships with integrase inhibitor-based initial antiretroviral therapy among persons with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e2234-e2242.

doi pubmed - Zhu S, Wang W, He J, Duan W, Ma X, Guan H, Wu Y, et al. Higher cardiovascular disease risks in people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2024;14:04078.

doi pubmed - Spieler G, Westfall AO, Long DM, Cherrington A, Burkholder GA, Funderburg N, Raper JL, et al. Trends in diabetes incidence and associated risk factors among people with HIV in the current treatment era. AIDS. 2022;36(13):1811-1818.

doi pubmed - Sax PE, Erlandson KM, Lake JE, McComsey GA, Orkin C, Esser S, Brown TT, et al. Weight gain following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: risk factors in randomized comparative clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1379-1389.

doi pubmed - Ruderman SA, Crane HM, Nance RM, Whitney BM, Harding BN, Mayer KH, Moore RD, et al. Brief report: weight gain following ART initiation in ART-naive people living with HIV in the current treatment era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(3):339-343.

doi pubmed - Emond B, Rossi C, Rogers R, Lefebvre P, Lafeuille MH, Donga P. Real-world analysis of weight gain and body mass index increase among patients with HIV-1 using antiretroviral regimen containing tenofovir alafenamide, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, or neither in the United States. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2022;9(1):39-49.

doi pubmed - Lam JO, Leyden WA, Alexeeff S, Lea AN, Hechter RC, Hu H, Marcus JL, et al. Changes in body mass index over time in people with and without HIV infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024;11(2):ofad611.

doi pubmed - Msoka T, Rogath J, Van Guilder G, Kapanda G, Smulders Y, Tutu van Furth M, Bartlett J, et al. Comparison of predicted cardiovascular risk profiles by different CVD risk-scoring algorithms between HIV-1-infected and uninfected adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in Tanzania. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2021;13:605-615.

doi pubmed - Baker JV, Duprez D, Rapkin J, Hullsiek KH, Quick H, Grimm R, Neaton JD, et al. Untreated HIV infection and large and small artery elasticity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(1):25-31.

doi pubmed - Iqbal J, Wu HX, Hu N, Zhou YH, Li L, Xiao F, Wang T, et al. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on body weight in adults with obesity without diabetes mellitus-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Obes Rev. 2022;23(6):e13435.

doi pubmed - Wong HJ, Sim B, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chan MY, Yeo LLL, Eng PC, et al. Efficacy of GLP-1 receptor agonists on weight loss, BMI, and waist circumference for patients with obesity or overweight: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 47 randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(2):292-300.

doi pubmed - Watanabe JH, Kwon J, Nan B, Reikes A. Trends in glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist use, 2014 to 2022. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2024;64(1):133-138.

doi pubmed - Berning P, Adhikari R, Schroer AE, Jelwan YA, Razavi AC, Blaha MJ, Dzaye O. Longitudinal analysis of obesity drug use and public awareness. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(1):e2457232.

doi pubmed - Khan MA, Gupta KK, Singh SK. A review on pharmacokinetics properties of antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV-1 infections. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2021;17(7):850-864.

doi pubmed - Jensen L, Helleberg H, Roffel A, van Lier JJ, Bjornsdottir I, Pedersen PJ, Rowe E, et al. Absorption, metabolism and excretion of the GLP-1 analogue semaglutide in humans and nonclinical species. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;104:31-41.

doi pubmed - Barnett TE. Glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists: safe and effective for people with HIV? Doctoral Dissertation, Keiser University; 2025.

- Bottanelli M, Galli L, Guffanti M, Castagna A, Muccini C. Are glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists effective in decreasing body weight and body mass index in people living with diabetes and HIV? HIV Med. 2024;25(3):404-406.

doi pubmed - Eckard AR, Wu Q, Sattar A, Ansari-Gilani K, Labbato D, Foster T, Fletcher AA, et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in people with HIV-associated lipohypertrophy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b single-centre clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(8):523-534.

doi pubmed - Haidar L, Crane HM, Nance RM, Webel A, Ruderman SA, Whitney BM, Willig AL, et al. Weight loss associated with semaglutide treatment among people with HIV. AIDS. 2024;38(4):531-535.

doi pubmed - Lake JE, Kitch DW, Kantor A, Muthupillai R, Klingman KL, Vernon C, Belaunzaran-Zamudio PF, et al. The effect of open-label semaglutide on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in people with HIV. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(6):835-838.

doi pubmed - Nguyen Q, Wooten D, Lee D, Moreno M, Promer K, Rajagopal A, Tan M, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists promote weight loss among people with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;79(4):978-982.

doi pubmed - Nazarenko N. Evaluation of weight reduction and metabolic parameters in HIV cohort undergoing treatment with GLP-1 receptor agonists at a large public NYC/HHC+ hospital in New York City. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2024;19:100788.

- Cattaneo D, Ridolfo AL, Giacomelli A, Cossu MV, Dolci A, Gori A, Antinori S, et al. Impact of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists on body weight in people with HIV and diabetes treated with integrase inhibitors. Diabetology. 2025;6(3):20.

- Saeedi R, Dabirvaziri P, Nashta NF, Yousefi M, Guillemi S, Montaner J. Effects of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, on metabolic abnormalities and body weight in HIV-infected subjects with or without type 2 diabetes. J HIV AIDS. 2015;1(2).

- Behuhuma N, Gasa G, Derache A, Nhlapo B, Khumalo S, Lam M, Khumalo P, et al. Liraglutide for obesity in HIV (LIROH): a clinical trial evaluating acceptability, impact on cardiometabolic risks & gut immunity of GLP-1 receptor agonists in South Africa: gut CD4 recovery. Presented at: IAS 2025, 13th IAS Conference on HIV Science; July 13-17, 2025; Kigali, Rwanda.

- Lloyd AN, Brizzi MB, Lyons MM, Rotert LM, Fichtenbaum CJ. Impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists on body weight in patients with type 2 diabetes and HIV. Presented at: IAS 2023, 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science; July 23-26, 2023; Brisbane, Australia.

- Sun J, Maheria P, Bramante C, Hsu V, Hurwitz E, Butzin-Dozier Z, Anzalone AJ, et al. Trajectories of weight changes after GLP-1 receptor agonists initiation among patients with HIV. Presented at: CROI 2025, Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 9-12, 2025; San Diego, CA.

- Vosoughi K, Roghani RS, Camilleri M. Effects of GLP-1 agonists on proportion of weight loss in obesity with or without diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Medicine. 2022;35:100456.

- Butale B, Woolley I, Cisera K, Korman T, Soldatos G. Under-utilisation of cardioprotective glucose-lowering medication in diabetics living with HIV. Sex Health. 2022;19(6):580-582.

doi pubmed - HHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents-A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. [Updated Sep 12, 2024]. In: ClinicalInfo.HIV.gov [Internet]. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2024.

- Bourgi K, Rebeiro PF, Turner M, Castilho JL, Hulgan T, Raffanti SP, Koethe JR, et al. Greater weight gain in treatment-naive persons starting dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(7):1267-1274.

doi pubmed - Pratley RE, Catarig AM, Lingvay I, Viljoen A, Paine A, Lawson J, Chubb B, et al. An indirect treatment comparison of the efficacy of semaglutide 1.0 mg versus dulaglutide 3.0 and 4.5 mg. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(11):2513-2520.

doi pubmed - Wen J, Nadora D, Bernstein E, How-Volkman C, Truong A, Akhtar M, Prakash NA, et al. Semaglutide versus other glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists for weight loss in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69008.

doi pubmed - Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, Hoy JF, Landovitz RJ, Mugavero MJ, Sax PE, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2018 recommendations of the international antiviral society-USA panel. JAMA. 2018;320(4):379-396.

doi pubmed - Hyle EP, Martey EB, Bekker LG, Xu A, Parker RA, Walensky RP, Middelkoop K. Diet, physical activity, and obesity among ART-experienced people with HIV in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2023;35(1):71-77.

doi pubmed - Nazarenko N, Chen YY, Borkowski P, Biavati L, Parker M, Vargas-Pena C, Chowdhury I, et al. Weight and mortality in people living with HIV and heart failure: Obesity paradox in the era of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. HIV Med. 2025;26(4):581-591.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cellular and Molecular Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.